Nieuws

« Terug naar overzichtPredicting the Future of Mediation (by Peter Adler)

We have agreed with Peter Adler to publish his article on the future of mediation on the website of Mediation Kamer Amsterdam. This article was written originally for www.mediate.com.

Peter Adler is a planner and mediator and a principal in The ACCORD3.0 Network, a professional group specializing in public policy collaboration. Adler has worked in the government, business, and NGO sectors and teaches advanced negotiation courses at the University of Hawaii

PREDICTING THE FUTURE OF MEDIATION

A Speculation and Entertainment by

Peter S. Adler, PhD [1]

“We are ready for any unforeseen event that may or may not occur.” -Vice President J. Danforth Quayle

The Very Chancy Business of Prediction

I should know better and follow the advice a friend once gave me when he said: “Peter, a shut mouth gathers no foot.” On the other hand, who in the world could possibly resist an invitation from www.mediate.com to opine on the future of something near and dear to my heart and happily rekindle some old quarrels with colleagues? Still, I fear no good things will come of this and it will be a rapid descent into some not so good company.

In the early 19th century an English aristocrat working for the British Raj in India noted after a trip back to London that the telegraph and telephone were interesting inventions but they would never take hold because of a surplus of messenger boys in the colonies. Then there was William Thompson, aka Lord Kelvin, the most famous English scientist of his time, who proudly pronounced: “Radiation has no future. Heavier-than-air flying machines are impossible. X-rays will prove to be a hoax.” And of course Sir Richard Van Der Reit Wooley, The Astronomer Royal, who in 1956 said, “Space travel is utter bilge.”

Lest you think only the English stumble in this area, there have also been plenty of misses by our people. In 1903 the president of the Michigan Savings Bank strongly advised Henry Ford’s lawyer not to invest in the Ford Motor Company. “The horse is here to stay but the automobile is only a novelty—a fad.” About that time as the era of silent films was coming to a close, Harry Warner, founder of Warner Brothers Studio, confidently said: “Who the hell wants to hear actors talk?” Later, inventor Lee Deforest noted “While theoretically and technically television may be feasible, commercially and financially I consider it an impossibility.” And Thomas Watson, chairman of IBM, who self-assuredly predicted there would be no real market for computers.

As a public policy mediator, here are three of my big predictions. First, no one is really going to get concerned about the world’s rapidly diminishing water quality until it affects the beer supply. Second, pesticide contamination won’t become a serious issue until it interferes with routers and Internet signals. And finally, when the oil and gas run out and hydrogen fuels prove impossible, we’ll power machines with urine vapor.

The Fog of Mediation

Radiation, cars, telecom gadgets, space ships, and computers, those are the easy ones. Mediation? Tougher. Why? Because mediation (a) isn’t a discrete “thing”; (b) what it is sits in the eye of the beholder and we beholders do very different things; and (c) the perfections we associate with our own particular gospels of mediation are perpetually marred by the contrary truths held by others who are just as smart, experienced, and knowledgeable as we are. You might as well ask what the future of “beauty” or “truth” is. Its that kind of problem.

In the late 1970s when I was trying to have it both ways and (a) be persuasive to the mediation-ignorant hoi palloi and (b) foster some substantiating research out of the university, I wrote down twenty sociological and legal assertions about mediation that I thought could be reframed as hypotheses. What I wrote was “Mediation is a better way of handling disputes because:

- It enhances participation by allowing more people to be involved in the process;

- It allows for flexibility in creating different ways for people to participate;

- It facilitates the disclosure and discovery of peoples real needs and interests

- It produces more options for consideration;

- It helps isolate mutual and overlapping interests;

- It allows for the creation of “bundles” of solutions and potential trades;

- It breaks impasse and gridlock;

- It helps manage, restore, and prevent loss of face;

- It produces better and more immediately usable information;

- It helps identify the highest levels of optimization and efficiency (the Pareto Frontier);

- It transforms personal relationships and attitudes;

- It lowers unnecessary “heat” and creates more civil discourse;

- It reduces bipolar demonization;

- It allows for great attention to the affective dimensions of a dispute;

- It infuses optimism and creativity into disputing situations.

- It helps create the ability to work together in the future;

- It helps create decisions that are more “transparent”, i.e., we can understand their logic and how they are reached;

- It allows people to find their own sense of “justice”;

- It saves money; and

- It saves time.”

Looking back, I can see I was far too energetic and theological about these assumptions and, frankly, wrong on most of them. Live and learn. Mediation has become a “reified” concept, an abstraction that we talk about as if it were a single grounded, empirical reality. Turns out we are in the realm of Plato’s cave where chained up people only see flickering shadows that they think are real people. That is why my twenty assumptions aren’t helpful. Mediation is situational and contextual and the devil is always in the details.

In mediation discussions at conferences all manner of often-inchoate things get spoken and lumped together to make up something even more inchoate. “Mediation” is a container into which people pour (and sometimes extract) collaborative law, citizen review panels, deliberative democracy, settlement hearings (in and out of court), collaborative governance, family conferencing, peer mediation, settlement weeks, joint fact-finding, and appreciative inquiry.

It also blends together the work lawyers, planners, accountants, and other professionals charge hundreds of dollars an hour to do along side that with community volunteers who are lucky enough to get gas money. Then, the conflation goes farther. It stirs in facilitated study groups, cross-sector roundtables, corporate inter-departmental task forces, conflict coaching, government appointed blue ribbon commissions, open dialogues, roundtables, and the technical best-practice consensus committees at NASA and the National Institutes of Health. All of this makes for a strange concoction, some kind of lemon-chocolate-vanilla-strawberry-pumpkin desert that is a sponge cake, a cheesecake, and a chicken potpie.

One manifestation of this confusion is the small side debate I have been having over the years as to whether all these ingredients brought together actually constitute a “field”. I have been in a number of discussions with colleagues like Bernie Mayer, Juliana Birkhofff, and Robert Benjamin who have said, “the field should unbundle its work” or “the field should embrace everyone who is doing peacemaking”, or “the field should recognize its own irrationality.”

With respect to my good friends Bernie, Juliana and Robert, there is no field. Mediation seems to be almost anything people want to claim it is, including me. At its simplest, all the diverse activities mentioned above can be rolled into something called “Assisted Negotiation”. But even that fails. What about where the goal is not negotiation, but communication or clearing the air? What about where the objective is reviewing research on a particular subject or where one side simply wants to issue an ultimatum? What about prayer sessions by people who are in pain or the world of Hawaiian ho’oponopono that I was originally trained in and which can be fairly dictatorial?

Everyone I know has their own approach to all this and many seem to have elements that seem universal, others that are individual depending on what the practitioner professes, and a few that are uniquely idiosyncratic. For me, it comes down to the particulars of what someone is purporting to do and the storyboard of who they are doing it to or for, when and where it is done, and how and why. Do all these constitute something common? Maybe they are kindred spirits, second or third cousins, but they aren’t the same thing.

A few years ago I wrote an article for www.mediate.com called “The End of Mediation: A Ramble on Why the Field Will Fail and Mediators Will Thrive over the Next Two Decades!” [2] I wrote it mainly to annoy a few people who were talking too boldly about “we practitioners” and “all of us mediators” and, sure enough, I got some peeved e-mails. One person wrote: “Peter, if there is no field, what have I been doing for the last 25 years?” I wrote back. “I have no idea what you do and you don’t know what I do and we have no idea how similar or different we are.”

Images of the Future

If I have learned anything, I know for sure that the future never turns out quite the way I predict. It is neither a precise continuation of the past nor something that can be planned without peripherally considering unexpected wild cards and sudden political, social, and economic pivots. Given how prismatic and kaleidoscopic the thing we call “mediation” is, any number of futures are possible. Here is my sense of it.

If we are talking broadly about all the cake ingredients that make up “Assisted Negotiation” then the future is extraordinarily bright. The complexities of decision-making in all manner of routine daily matters of life are getting more bureaucratic and entangled. Comedienne Lily Tomlin once said she thought humans originally developed a language capacity because of a deep-seated need to complain. In all the disgruntlement, irritation, annoyance, and argument, some people will always, as a final and last resort, want navigators to help sort out the discord when their own strategies fail.

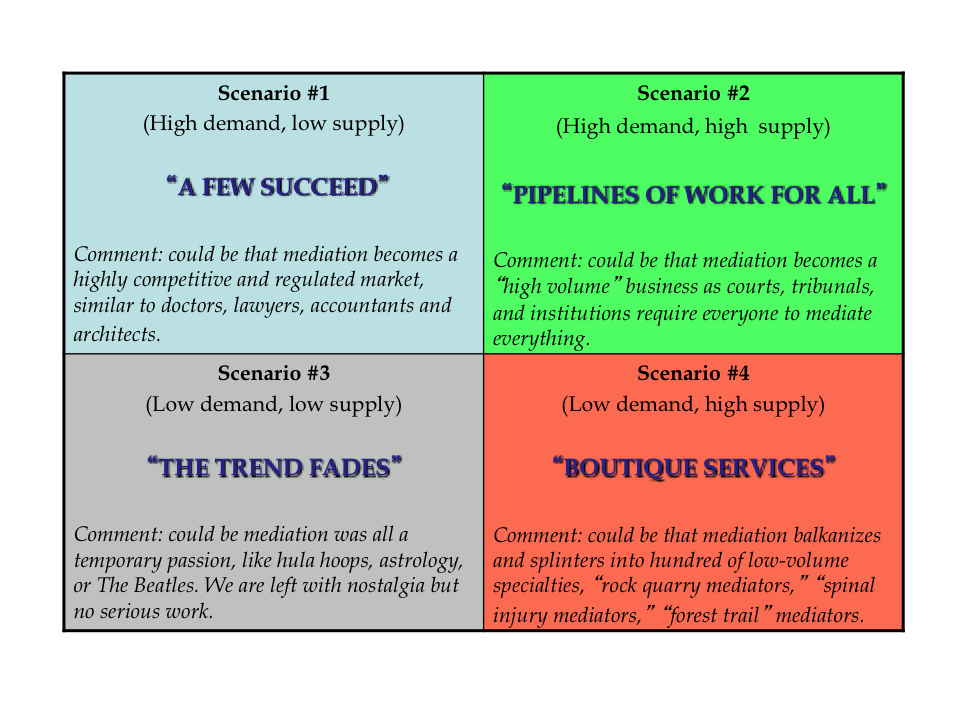

As for the versions of mediation that have been institutionalized by tribunal managers, marketed and sold by trainers, taught by university professors and eagerly lapped up by people who want paid work, I can envision at least four different futures that are variations of possible “supply” and “demand” factors and that build off the 2-by-2 matrices futurists sometimes use to concoct possible scenarios. Here are four possibilities:

A colleague in London, Michael Leathes, tells me there are two ignored lessons from the 1976 Pound Conference which he believes was the “Big Bang” that started the current wave of mediation practice and that he also believes will culminate in an elite set of international professionals. The first clue, Michael argues, was in the title of Chief Justice Warren Berger’s keynote address: “The Need for Systematic Anticipation.” The second was an alarm bell sounded by Frank Sander who said that the one thing that could kill mediation was the slow death of status quo-ism. I fear both of these may be going on now.[3]

As we grow to a planet of 9-billion people (after which population is expected to level off) I know the work I and my ACCORD3.0 colleagues do to collaboratively attack stubborn public policy problems is accelerating and intensifying. The World Economic Forum (WEF) reports the top ten global risks we all currently face are:

- Fiscal crises in key economies

- Structurally high unemployment/underemployment

- Water crises

- Severe income disparity

- Failure of climate change mitigation and adaptation

- Greater incidence of extreme weather events (e.g. floods, storms, fires)

- Global governance failures

- Food crises

- Failures of major financial institutions

- Profound political and social instability [4]

When Willie Sutton, a renowned American thief, was asked why he became a bank robber his answer was: “That’s where the money is.” Courts have been rapid adopters because they are “the banks”, the low hanging fruit where the disputes have form, deadlines, and consequence. As Jeff Krivis once noted, mediation is now fully married into the civil procedures of the U.S. and a few other countries. But that is not the end of the journey that started long before the Pound conference.

The new frontiers for those of us who are questing for a better kind of politics sit in (a) the political and regulatory arenas where so many of our rules, standards, policies and plans are actually set and (b) the cultures we each swim in. The best definition of culture I ever heard is: “culture is the way we do things around here.” The exact form of how mediation will be further adapted isn’t clear but what we do know is this. Assisted negotiation has been around for a long time and we will not be running out of disputes and brouhahas and ever more innovative and protean ways to work with them. The stakes will also keep getting higher which intensifies the need.

So blessed are the peacemakers. For those who are in it for the long haul, for whom it is a calling more than a field or profession, you won’t be running out of work anytime soon.

Footnotes:

[1] Peter S. Adler is a planner and mediator and a principal in The ACCORD3.0 Network, a professional group specializing in public policy collaboration. Adler has worked in the government, business, and NGO sectors and teaches advanced negotiation courses at the University of Hawaii. Prior executive experience includes nine years as President and CEO of The Keystone Center, Executive Director of the Hawai‘i Justice Foundation, and founding Director of the Hawai‘i Supreme Court’s Center for Alternative Dispute Resolution. He is the author of three books and numerous academic and popular articles. He lives and works in Hawai‘i and can be reached at padleraccord@gmail.com or 808-888-0215

[2] http://www.mediate.com/articles/adlerTheEnd.cfm

[3] https://imimediation.org/2020-vision-article

[4] See “Global Risks 2014 Ninth Edition,” The World Economic Forum at www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GlobalRisks_Report_2014.pdf